1.2: Реальні числа - Основи алгебри

- Page ID

- 59603

- Класифікувати дійсне число як натуральне, ціле, ціле, раціональне або ірраціональне число.

- Виконуйте розрахунки, використовуючи порядок операцій.

- Використовуйте такі властивості дійсних чисел: комутативні, асоціативні, розподільні, обернені та ідентичні.

- Оцініть алгебраїчні вирази.

- Спрощення алгебраїчних виразів.

Часто говорять, що математика - це мова науки. Якщо це правда, то мова математики - числа. Найбільш раннє використання чисел відбулося\(100\) століття тому на Близькому Сході для підрахунку або перерахування предметів. Фермери, скотарі та торговці використовували жетони, камені або маркери, щоб позначити одну кількість - сніп зерна, голову худоби або тканину фіксованої довжини, наприклад. Це зробило можливою торгівлю, що призвело до поліпшення комунікацій та поширення цивілізації.

Три-чотири тисячі років тому єгиптяни вводили фракції. Вони вперше використовували їх, щоб показати взаємні. Пізніше вони використовували їх для представлення суми, коли кількість ділилася на рівні частини.

Але що робити, якщо не було великої рогатої худоби, щоб торгувати або цілий урожай зерна загинув під час потопу? Як хтось міг вказувати на існування нічого? З найдавніших часів люди думали про «базовий стан» під час підрахунку і використовували різні символи для представлення цього нульового стану. Однак приблизно в п'ятому столітті нашої ери в Індії нуль був доданий до системи числення і використовувався як числівник при розрахунках.

Зрозуміло, що також виникла потреба в цифрах, які представляють збитки або борг. В Індії в сьомому столітті нашої ери від'ємні числа використовувалися як рішення математичних рівнянь і комерційних боргів. Протилежності рахункових чисел ще більше розширили систему числення.

Через еволюцію системи числення тепер ми можемо виконувати складні обчислення, використовуючи ці та інші категорії дійсних чисел. У цьому розділі ми розглянемо набори чисел, обчислення з різними видами чисел, а також використання чисел у виразах.

Класифікація дійсного числа

Цифри, які ми використовуємо для підрахунку, або перерахування елементів, - це натуральні числа:\(1, 2, 3, 4, 5\) і так далі. Ми описуємо їх у множинних позначеннях як\(\{1,2,3,...\}\) де крапка\((\cdots)\) вказує на те, що числа продовжуються до нескінченності. Натуральні числа, звичайно, також називають числами підрахунку. Кожен раз, коли ми перераховуємо членів команди, підраховуємо монети в колекції або підраховуємо дерева в гаю, ми використовуємо набір натуральних чисел. Множина цілих чисел - це набір натуральних чисел плюс нуль:\(\{0,1,2,3,...\}\).

Безліч цілих чисел додає протилежності натуральних чисел до множини цілих чисел:\(\{\cdots,-3,-2,-1,0,1,2,3,\cdots\}\). Корисно відзначити, що набір цілих чисел складається з трьох різних підмножин: від'ємні цілі числа, нуль і натуральні числа. У цьому сенсі позитивні цілі числа - це лише натуральні числа. Інший спосіб подумати про це полягає в тому, що натуральні числа є підмножиною цілих чисел.

\[ \overbrace{\cdots, -3,-2,-1}^{\text{negative integers}}, \underbrace{0}_{\text{zero}}, \overbrace{1,\, 2,\,3,\, \cdots}^{\text{positive integers}} \nonumber\]

Набір раціональних чисел пишеться як\(\{\frac{m}{n}| \text{m and n are integers and } n \neq 0\}\) .Зверніть увагу з визначення, що раціональні числа - це дроби (або частки), що містять цілі числа як в чисельнику, так і в знаменнику, а знаменник ніколи\(0\). Ми також можемо бачити, що кожне натуральне число, ціле число і ціле є раціональним числом зі знаменником\(1\).

Оскільки вони є дробами, будь-яке раціональне число також може бути виражено в десятковій формі. Будь-яке раціональне число можна представити як:

- закінчення десяткового числа:\(\frac{15}{8} =1.875\), або

- повторювана десяткова кома:\(\frac{4}{11} =0.36363636\cdots = 0.\bar{36}\)

Ми використовуємо лінію, намальовану над повторюваним блоком чисел, замість того, щоб писати групу кілька разів.

Запишіть кожне з наступних як раціональне число. Запишіть дріб з цілим числом в чисельнику і\(1\) in the denominator.

- \(7\)

- \(0\)

- \(-8\)

Рішення

а.\(7= \frac{7}{1}\)

б.\(0= \frac{0}{1}\)

c.\(-8= \frac{-8}{1}\)

Запишіть кожне з наступних як раціональне число.

- \(11\)

- \(3\)

- \(-4\)

- Відповідь

-

- \(\frac{11}{1}\)

- \(\frac{3}{1}\)

- \(-\frac{4}{1}\)

Запишіть кожне з наступних раціональних чисел як кінцеве або повторюване десяткове число.

- \(-\frac{5}{7}\)

- \(\frac{15}{5}\)

- \(\frac{13}{25}\)

Рішення

a. повторювана десяткова

b.\(\frac{15}{5} = 3\) (або\(3.0\)), закінчення десяткового

c.\(\frac{13}{25} =0.52\), що закінчується десятковий

Запишіть кожне з наступних раціональних чисел як кінцеве або повторюване десяткове число.

- \(\frac{68}{17}\)

- \(\frac{8}{13}\)

- \(-\frac{13}{25}\)

- Відповідь

-

- \(4\)(або\(4.0\)), припиняючи

- \(0.\overline{615384}\), повторюючи

- \(-0.85\), припиняючи

Ірраціональні числа

У якийсь момент стародавнього минулого хтось виявив, що не всі числа є раціональними числами. Наприклад, будівельник, можливо, виявив, що діагональ квадрата з одиничними сторонами не була\(2\) або навіть\(32\), але була чимось іншим. Або швейний майстер міг спостерігати, що відношення окружності до діаметра рулону тканини було трохи більше\(3\), але все ж не раціональне число. Такі числа вважаються ірраціональними, оскільки їх не можна записати як дроби. Ці числа складають набір ірраціональних чисел. Ірраціональні числа не можуть бути виражені у вигляді дробу двох цілих чисел. Неможливо описати цей набір чисел одним правилом, крім як сказати, що число нераціонально, якщо воно не є раціональним. Таким чином, ми пишемо це, як показано.

\[\{h\mid h \text { is not a rational number}\}\]

Визначте, чи є кожне з наступних чисел раціональним чи ірраціональним. Якщо це раціонально, визначте, чи є він кінцевим або повторюваним десятковим.

- \(\sqrt{25}\)

- \(\frac{33}{9}\)

- \(\sqrt{11}\)

- \(\frac{17}{34}\)

- \(0.3033033303333…\)

Рішення

- \(\sqrt{25}\): Це можна спростити як\(\sqrt{25} = 5\) .Тому\(\sqrt{25}\) раціонально.

- \(\frac{33}{9}\): Оскільки це дріб,\(\frac{33}{9}\) є раціональним числом. Далі спростити і розділити. \[\frac{33}{9}=\cancel{\frac{33}{9}} \nonumber\]Отже,\(\frac{33}{9}\) є раціональним і повторюваним десятковим.

- \(\sqrt{11}\): Це не може бути спрощено далі. Тому\(\sqrt{11}\) є ірраціональним числом.

- \(\frac{17}{34}\): Оскільки це дріб,\(\frac{17}{34}\) є раціональним числом. Спростити і розділити. \[\frac{17}{34} = 0.5 \nonumber\]Отже,\(\frac{17}{34}\) є раціональним і закінчується десятковим.

- \(0.3033033303333…\)не є кінцевою десятковою. Також зверніть увагу, що немає повторюваного шаблону, оскільки група\(3s\) збільшується з кожним разом. Тому це не є ні кінцевим, ні повторюваним десятковим і, отже, не раціональним числом. Це ірраціональне число.

Визначте, чи є кожне з наступних чисел раціональним чи ірраціональним. Якщо це раціонально, визначте, чи є він кінцевим або повторюваним десятковим.

- \(\frac{7}{77}\)

- \(\sqrt{81}\)

- \(4.27027002700027…\)

- \(\frac{91}{13}\)

- \(\sqrt{39}\)

- Відповідь

-

- раціональні і повторювані;

- раціональний і кінцевий;

- ірраціональний;

- раціональний і кінцевий;

- ірраціональний

Реальні числа

З огляду на будь-яке число\(n\), ми знаємо, що\(n\) це або раціонально, або ірраціонально. Це не може бути і те, і інше. Множини раціональних і ірраціональних чисел разом складають безліч дійсних чисел. Як ми бачили з цілими числами, дійсні числа можна розділити на три підмножини: від'ємні дійсні числа, нуль та додатні дійсні числа. Кожна підмножина включає дроби, десяткові та ірраціональні числа відповідно до їх алгебраїчним знаком (+ або —). Нуль не вважається ні позитивним, ні негативним.

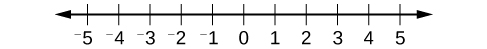

Реальні числа можна візуалізувати на горизонтальній числовій лінії з довільною точкою, обраною як\(0\), з від'ємними числами ліворуч від\(0\) та додатними числами праворуч від\(0\). Фіксована одинична відстань використовується для позначення кожного цілого числа (або іншого основного значення) по обидва боки\(0\). Будь-яке дійсне число відповідає унікальній позиції на числовій лінії. Зворотне також вірно: Кожне місце на числовому рядку відповідає рівно одному дійсному числу. Це відоме як листування один до одного. Ми називаємо це дійсним числовим рядком, як показано на малюнку (\(\PageIndex{1}\).

Класифікуйте кожне число як позитивне або негативне і як раціональне або ірраціональне. Чи лежить число ліворуч або праворуч\(0\) на числовому рядку?

- \(-\frac{10}{3}\)

- \(-\sqrt{5}\)

- \(-6π\)

- \(0.615384615384…\)

Рішення

- \(-\frac{10}{3}\)негативний і раціональний. Вона лежить\(0\) зліва від номера рядка.

- \(-\sqrt{5}\)позитивний і нераціональний. Вона лежить праворуч від\(0\).

- \(-\sqrt{289} = -\sqrt{17^2} = -17\)негативний і раціональний. Він лежить зліва від\(0\).

- \(-6π\)негативний і ірраціональний. Він лежить зліва від\(0\).

- \(0.615384615384…\)є повторюваним десятковим, тому він раціональний і позитивний. Вона лежить праворуч від\(0\).

Класифікуйте кожне число як позитивне або негативне і як раціональне або ірраціональне. Чи лежить число ліворуч або праворуч\(0\) на числовому рядку?

- \(\sqrt{73}\)

- \(-11.411411411…\)

- \(\frac{47}{19}\)

- \(-\frac{\sqrt{5}}{2}\)

- \(6.210735\)

- Відповідь

-

- позитивний, ірраціональний

- правий негативний, раціональний

- залишив позитивний, раціональний

- правий негативний, ірраціональний

- ліва позитивна, раціональна; права

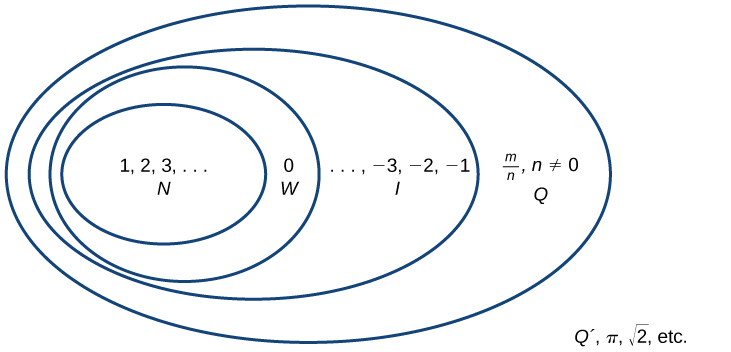

Множини чисел як підмножин

Починаючи з натуральних чисел, ми розширили кожен набір, щоб сформувати більший набір, це означає, що існує зв'язок підмножини між множинами чисел, з якими ми стикалися досі. Ці зв'язки стають більш очевидними, якщо розглядати як діаграму, наприклад, Figure (\(\PageIndex{2}\)).

Набір натуральних чисел включає в себе числа, використовувані для підрахунку:\(\{1,2,3,...\}\).

Множина цілих чисел - це набір натуральних чисел плюс нуль:\(\{0,1,2,3,...\}\).

Набір цілих чисел додає від'ємні натуральні числа до множини цілих чисел:\(\{...,-3,-2,-1,0,1,2,3,...\}\).

Множина раціональних чисел включає дроби, записані як\(\{\frac{m}{n} | \text{m and n are integers and } n \neq 0\}\).

Безліч ірраціональних чисел - це сукупність чисел, які не є раціональними, неповторюваними і є нескінченними:\(\{h\parallel \text{h is not a rational number}\}\).

Класифікуйте кожне число як натуральне число (N), ціле число (W), ціле число (I), раціональне число (Q) та/або ірраціональне число (Q′).

- \(\sqrt{36}\)

- \(\frac{8}{3}\)

- \(\sqrt{73}\)

- \(-6\)

- \(3.2121121112…\)

Рішення

| П | Ш | Я | Q | Q' | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| а.\(\sqrt{36} = 6\) | Х | Х | Х | Х | |

| б.\(\frac{8}{3} =2.\overline{6}\) | Х | ||||

| c.\(\sqrt{73}\) | Х | ||||

| д.\(-6\) | Х | Х | |||

| е.\(3.2121121112...\) | Х |

Класифікуйте кожне число як натуральне число (N), ціле число (W), ціле число (I), раціональне число (Q) та/або ірраціональне число (Q′).

- \(-\frac{35}{7}\)

- \(0\)

- \(\sqrt{169}\)

- \(\sqrt{24}\)

- \(4.763763763...\)

- Відповідь

-

П Ш Я Q Q' а.\(-\frac{35}{7}\) Х Х б.\(0\) Х Х Х c.\(\sqrt{169}\) Х Х Х Х д.\(\sqrt{24}\) Х е.\(4.763763763...\) Х

Виконання розрахунків з використанням порядку операцій

Коли ми множимо число саме по собі, ми квадратично його або піднімаємо його до сили\(2\). Наприклад,\(4^2 =4\times4=16\). Ми можемо підняти будь-яке число до будь-якої сили. Загалом, експоненціальне позначення an означає, що число або змінна\(a\) використовується як множник\(n\) раз.

\[a^n=a\cdot a\cdot a\cdots a \qquad \text{ n factors} \nonumber \]

У цьому позначенні,\(a^n\) читається як\(n^{th}\) сила\(a\), де\(a\) називається базою і\(n\) називається експонентою. Термін в експоненціальному позначенні може бути частиною математичного виразу, що представляє собою комбінацію чисел і операцій. Наприклад,\(24+6 \times \dfrac{2}{3} − 4^2\) це математичний вираз.

Для оцінки математичного виразу виконуємо різні операції. Однак ми не виконуємо їх в будь-якому випадковому порядку. Використовуємо порядок операцій. Це послідовність правил оцінки таких виразів.

Нагадаємо, що в математиці ми використовуємо дужки (), дужки [] та фігурні дужки {} для групування чисел і виразів так, щоб все, що з'являється всередині символів, розглядалося як одиниця. Крім того, смуги дробів, радикалів та абсолютних значень розглядаються як символи групування. При оцінці математичного виразу почніть зі спрощення виразів всередині угруповання символів.

Наступним кроком є вирішення будь-яких експонентів або радикалів. Після цього виконайте множення та ділення зліва направо і, нарешті, додавання та віднімання зліва направо.

Давайте подивимося на надане вираз.

\[24+6 \times \dfrac{2}{3} − 4^2 \nonumber\]

Угруповання символів немає, тому ми переходимо до експонентів або радикалів. Число\(4\) піднімається в силу\(2\), так спростити\(4^2\) як\(16\).

\[24+6 \times \dfrac{2}{3} − 4^2 \nonumber \]

\[24+6 \times \dfrac{2}{3} − 16 \nonumber\]

Далі виконуємо множення або ділення, зліва направо.

\[24+6 \times \dfrac{2}{3} − 16 \nonumber\]

\[24+4-16 \nonumber\]

Нарешті, виконайте додавання або віднімання зліва направо.

\[24+4−16 \nonumber\]

\[28−16 \nonumber\]

\[12 \nonumber\]

Тому

\[24+6 \times \dfrac{2}{3} − 4^2 =12 \nonumber\]

Для деяких складних виразів знадобиться кілька проходів по порядку операцій. Наприклад, всередині дужок може бути радикальний вираз, який потрібно спростити перед оцінкою дужок. Дотримання порядку операцій гарантує, що кожен, хто спрощує один і той же математичний вираз, отримає однаковий результат.

Операції в математичних виразах повинні оцінюватися в систематичному порядку, який можна спростити за допомогою абревіатури PEMDAS:

- P (арентези)

- E (компоненти)

- M (множення) і D (поділ)

- A (додавання) і S (віднімання)

- Спростіть будь-які вирази в групуванні символів.

- Спростіть будь-які вирази, що містять експоненти або радикали.

- Виконайте будь-яке множення і ділення по порядку, зліва направо.

- Виконайте будь-яке додавання і віднімання по порядку, зліва направо.

Використовуйте порядок операцій для обчислення кожного з наступних виразів.

- \(\dfrac{5^2-4}{7}- \sqrt{11-2}\)

- \(\dfrac{14-3 \times2}{2 \times5-3^2}\)

- \(7\times(5\times3)−2\times[(6−3)−4^2]+1\)

Рішення

- \[\begin{align*} (3\times2)^2-4\times(6+2)&=(6)^2-4\times(8) && \qquad \text{Simplify parentheses}\\ &=36-4\times8 && \qquad \text{Simplify exponent}\\ &=36-32 && \qquad \text{Simplify multiplication}\\ &=4 && \qquad \text{Simplify subtraction}\\ \end{align*}\]

- \[\begin{align*} \dfrac{5^2-4}{7}- \sqrt{11-2}&= \dfrac{5^2-4}{7}-\sqrt{9} && \qquad \text{Simplify grouping symbols (radical)}\\ &=\dfrac{5^2-4}{7}-3 && \qquad \text{Simplify radical}\\ &=\dfrac{25-4}{7}-3 && \qquad \text{Simplify exponent}\\ &=\dfrac{21}{7}-3 && \qquad \text{Simplify subtraction in numerator}\\ &=3-3 && \qquad \text{Simplify division}\\ &=0 && \qquad \text{Simplify subtraction} \end{align*}\]

Зверніть увагу, що на першому кроці радикал розглядається як символ угруповання, як дужки. Також на третьому кроці брусок дробу вважається символом угруповання, тому чисельник вважається згрупованим.

- \[\begin{align*} 6-\mid 5-8\mid +3\times(4-1)&=6-|-3|+3\times3 && \qquad \text{Simplify inside grouping symbols}\\ &=6-3+3\times3 && \qquad \text{Simplify absolute value}\\ &=6-3+9 && \qquad \text{Simplify multiplication}\\ &=3+9 && \qquad \text{Simplify subtraction}\\ &=12 && \qquad \text{Simplify addition}\\ \end{align*}\]

- \[\begin{align*} \dfrac{14-3 \times2}{2 \times5-3^2}&=\dfrac{14-3 \times2}{2 \times5-9} && \qquad \text{Simplify exponent}\\ &=\dfrac{14-6}{10-9} && \qquad \text{Simplify products}\\ &=\dfrac{8}{1} && \qquad \text{Simplify differences}\\ &=8 && \qquad \text{Simplify quotient}\\ \end{align*}\]

У цьому прикладі рядок дробу розділяє чисельник і знаменник, які ми спрощуємо окремо до останнього кроку.

- \[\begin{align*} 7\times(5\times3)-2\times[(6-3)-4^2]+1&=7\times(15)-2\times[(3)-4^2]+1 && \qquad \text{Simplify inside parentheses}\\ &=7\times(15)-2\times(3-16)+1 && \qquad \text{Simplify exponent}\\ &=7\times(15)-2\times(-13)+1 && \qquad \text{Subtract}\\ &=105+26+1 && \qquad \text{Multiply}\\ &=132 && \qquad \text{Add} \end{align*}\]

Використовуйте порядок операцій для обчислення кожного з наступних виразів.

- \(\sqrt{5^2-4^2}+7\times(5-4)^2\)

- \(1+\dfrac{7\times5-8\times4}{9-6}\)

- \(|1.8-4.3|+0.4\times\sqrt{15+10}\)

- \(\dfrac{1}{2}\times[5\times3^2-7^2]+\dfrac{1}{3}\times9^2\)

- \([(3-8^2)-4]-(3-8)\)

- Відповідь

-

- \(10\)

- \(2\)

- \(4.5\)

- \(25\)

- \(26\)

Використання властивостей дійсних чисел

Для деяких дій, які ми виконуємо, порядок певних операцій не має значення, але порядок інших операцій робить. Наприклад, не має значення, якщо ми одягаємо праву взуття перед лівою або навпаки. Однак неважливо, одягаємо ми спочатку взуття чи шкарпетки. Те ж саме справедливо і для операцій з математики.

Комутативні властивості

Комутативна властивість додавання говорить, що числа можуть додаватися в будь-якому порядку, не впливаючи на суму.

\[a+b=b+a\]

Ми можемо краще бачити цей зв'язок при використанні реальних чисел.

\((−2)+7 = 5 \text{ and } 7+(−2)=5\)

Аналогічно комутативне властивість множення стверджує, що числа можна множити в будь-якому порядку, не впливаючи на твір.

\[a\times b=b\times a\]

Знову ж таки, розглянемо приклад з дійсними числами.

Важливо відзначити, що ні віднімання, ні ділення не є комутативними. Наприклад,\(17−5\) це не те ж саме, що\(5−17\). Аналогічно,\(20÷5≠5÷20\).

асоціативні властивості

Асоціативне властивість множення говорить нам про те, що не має значення, як ми групуємо числа при множенні. Ми можемо переміщати символи групування, щоб полегшити розрахунок, а продукт залишається тим самим.

\[a(bc)=(ab)c\]

Розглянемо цей приклад.

\((3\times4)\times5=60 \text{ and } 3\times(4\times5)=60\)

Асоціативна властивість додавання говорить нам про те, що числа можуть бути згруповані по-різному, не впливаючи на суму.

\[a+(b+c)=(a+b)+c\]

Ця властивість може бути особливо корисною при роботі з негативними цілими числами. Розглянемо цей приклад.

\([15+(−9)]+23=29 \text{ and } 15+[(−9)+23]=29\)

Чи асоціативні віднімання та поділ? Перегляньте ці приклади.

\[\begin{align*} 8-(3-15)\overset{?}{=}&(8-3)-15\\ 8-(-12)\overset{?}{=}&5-15\\ 20 \neq &10\\ 64\div (8\div 4)\overset{?}{=}&(64\div 8)\div 4\\ 64\div 2\overset{?}{=}&8\div 4\\ 32 \neq & 2 \end{align*}\]

Як бачимо, ні віднімання, ні поділ не асоціативні.

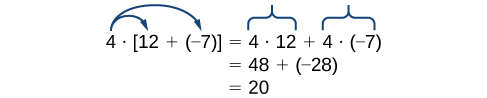

Розподільна власність

Розподільна властивість стверджує, що добуток множника на суму є сумою множника на кожен член в сумі.

\[a\times(b+c)=a\times b+a\times c\]

Ця властивість поєднує в собі як додавання, так і множення (і є єдиною властивістю для цього). Розглянемо приклад.

Зауважте, що\(4\) is outside the grouping symbols, so we distribute the \(4\) by multiplying it by \(12\), multiplying it by \(–7\), and adding the products.

To be more precise when describing this property, we say that multiplication distributes over addition. The reverse is not true, as we can see in this example.

\[\begin{align*} 6+(3\times5)\overset{?}{=}&(6+3)\times(6\times5)\\ 6+(15)\overset{?}{=}&(9)\times(11)\\ 21 \neq &99 \end{align*}\]

Multiplication does not distribute over subtraction, and division distributes over neither addition nor subtraction.

A special case of the distributive property occurs when a sum of terms is subtracted.

\[a−b=a+(−b)\]

For example, consider the difference \(12−(5+3)\). We can rewrite the difference of the two terms \(12\) and \((5+3)\) by turning the subtraction expression into addition of the opposite. So instead of subtracting \( (5+3)\), we add the opposite.

Now, distribute \(-1\) and simplify the result.

\[\begin{align*} 12-(5+3)&=12+(-1)\times(5+3)\\ &=12+[(-1)\times5+(-1)\times3]\\ &=12+(-8)\\ &=4 \end{align*}\]

This seems like a lot of trouble for a simple sum, but it illustrates a powerful result that will be useful once we introduce algebraic terms. To subtract a sum of terms, change the sign of each term and add the results. With this in mind, we can rewrite the last example.

\[\begin{align*} 12-(5+3)&=12+(-5-3)\\ &=12-8\\ &=4 \end{align*}\]

Identity Properties

The identity property of addition states that there is a unique number, called the additive identity \((0)\) that, when added to a number, results in the original number.

\[a+0=a\]

The identity property of multiplication states that there is a unique number, called the multiplicative identity \((1)\) that, when multiplied by a number, results in the original number.

\[a\times 1=a\]

For example, we have \( (−6)+0=−6\) and\( 23\times1=23\). There are no exceptions for these properties; they work for every real number, including \(0\) and \(1\).

Inverse Properties

The inverse property of addition states that, for every real number a, there is a unique number, called the additive inverse (or opposite), denoted \(−a\), that, when added to the original number, results in the additive identity, \(0\).

\[a+(−a)=0\]

For example, if \(a =−8\), the additive inverse is \(8\), since \((−8)+8=0\).

The inverse property of multiplication holds for all real numbers except \(0\) because the reciprocal of \(0\) is not defined. The property states that, for every real number \(a\), there is a unique number, called the multiplicative inverse (or reciprocal), denoted \(1a\), that, when multiplied by the original number, results in the multiplicative identity, \(1\).

\[a\times \dfrac{1}{a}=1\]

For example, if \(a =−\dfrac{2}{3}\), the reciprocal, denoted \(\dfrac{1}{a}\), is \(-\dfrac{3}{2}\) because

\[a⋅\dfrac{1}{a}=\left(−\dfrac{2}{3}\right)\times\left(−\dfrac{3}{2}\right)=1 \nonumber\]

The following properties hold for real numbers \(a\), \(b\), and \(c\).

| Addition | Multiplication | |

|---|---|---|

| Commutative Property | \(a+b=b+a\) | \(a\times b=b\times a\) |

| Associative Property | \(a+(b+c)=(a+b)+c\) | \(a(bc)=(ab)c\) |

| Distributive Property | \(a\times (b+c)=a\times b+a\times c\) | |

| Identity Property |

There exists a unique real number called the additive identity, 0, such that, for any real number a \(a+0=a\)

|

There exists a unique real number called the multiplicative identity, 1, such that, for any real number a \(a\times 1=a\)

|

| Inverse Property |

Every real number a has an additive inverse, or opposite, denoted –a, such that \(a+(−a)=0\)

|

Every nonzero real number a has a multiplicative inverse, or reciprocal, denoted 1a , such that \(a\times \left(\dfrac{1}{a}\right)=1\)

|

Use the properties of real numbers to rewrite and simplify each expression. State which properties apply.

- \(3\times 6+3\times 4\)

- \((5+8)+(−8)\)

- \(6−(15+9)\)

- \(\dfrac{4}{7}\times\left(\dfrac{2}{3}\times \dfrac{7}{4}\right)\)

- \(100\times[0.75+(−2.38)]\)

Solution

- \[\begin{align*} 3\times6+3\times4&=3\times(6+4)\qquad \text{Distributive property}\\ &=3\times10\qquad \text{Simplify}\\ &=30\qquad \text{Simplify}\\ \end{align*}\]

- \[\begin{align*} (5+8)+(-8)&=5+[8+(-8)]\qquad \text{Associative property of addition}\\ &=5+0\qquad \text{Inverse property of addition}\\ &=5\qquad \text{Identity property of addition}\\ \end{align*}\]

- \[\begin{align*} 6-(15+9)&=6+[(-15)+(-9)]\qquad \text{Distributive property}\\ &=6+(-24)\qquad \text{Simplify}\\ &=-18\qquad \text{Simplify}\\ \end{align*}\]

- \[\begin{align*} \dfrac{4}{7}\times\left(\dfrac{2}{3}\times\dfrac{7}{4}\right)&=\dfrac{4}{7}\times\left(\dfrac{7}{4}\times\dfrac{2}{3}\right)\qquad \text{Commutative property of multiplication}\\ &=\left(\dfrac{4}{7}\times\dfrac{7}{4}\right)\times\dfrac{2}{3}\qquad \text{Associative property of multiplication}\\ &=1\times\dfrac{2}{3}\qquad \text{Inverse property of multiplication}\\ &=\dfrac{2}{3}\qquad \text{Identity property of multiplication}\\ \end{align*}\]

- \[\begin{align*} 100\times[0.75+(-2.38)]&=100\times0.75+100\times(-2.38)\qquad \text{Distributive property}\\ &=75+(-238)\qquad \text{Simplify}\\ &=-163\qquad \text{Simplify} \end{align*}\]

Use the properties of real numbers to rewrite and simplify each expression. State which properties apply.

- \(\left(-\dfrac{23}{5}\right)\times\left[11\times\left(-\dfrac{5}{23}\right)\right]\)

- \(5\times(6.2+0.4)\)

- \(18-(7-15)\)

- \(\dfrac{17}{18}+\left[\dfrac{4}{9}+\left(-\dfrac{17}{18}\right)\right]\)

- \(6\times(-3)+6\times3\)

- Answer

-

- \(11)\), commutative property of multiplication

- \(33\), distributive property

- \(26\), distributive property

- \(\dfrac{4}{9}\), commutative property of addition, associative property of addition, inverse property of addition, identity property of addition

- \(0\), distributive property, inverse property of addition, identity property of addition

Evaluating Algebraic Expressions

So far, the mathematical expressions we have seen have involved real numbers only. In mathematics, we may see expressions such as \(x +5\), \(\dfrac{4}{3}\pi r^3\), or \(\sqrt{2m^3 n^2}\). In the expression \(x +5\), \(5\) is called a constant because it does not vary and \(x\) is called a variable because it does. (In naming the variable, ignore any exponents or radicals containing the variable.) An algebraic expression is a collection of constants and variables joined together by the algebraic operations of addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division.

We have already seen some real number examples of exponential notation, a shorthand method of writing products of the same factor. When variables are used, the constants and variables are treated the same way.

\[\begin{align*} (-3)^5 &=(-3)\times(-3)\times(-3)\times(-3)\times(-3)\Rightarrow x^5=x\times x\times x\times x\times x\\ (2\times7)^3&=(2\times7)\times(2\times7)\times(2\times7)\qquad \; \; \Rightarrow (yz)^3=(yz)\times(yz)\times(yz) \end{align*}\]

In each case, the exponent tells us how many factors of the base to use, whether the base consists of constants or variables.

Any variable in an algebraic expression may take on or be assigned different values. When that happens, the value of the algebraic expression changes. To evaluate an algebraic expression means to determine the value of the expression for a given value of each variable in the expression. Replace each variable in the expression with the given value, then simplify the resulting expression using the order of operations. If the algebraic expression contains more than one variable, replace each variable with its assigned value and simplify the expression as before.

List the constants and variables for each algebraic expression.

- \(x + 5\)

- \(\dfrac{4}{3}\pi r^3\)

- \(\sqrt{2m^3 n^2}\)

Solution

| Constants | Variables | |

|---|---|---|

| a. \(x + 5\) | \(5\) | \(x\) |

| b. \(\dfrac{4}{3}\pi r^3\) | \(\dfrac{4}{3}\), \(\pi\) | \(r\) |

| c. \(\sqrt{2m^3 n^2}\) | \(2\) | \(m\),\(n\) |

List the constants and variables for each algebraic expression.

- \(2(L + W)\)

- \(4y^3+y\)

- Answer

-

Constants Variables a. \(2\pi r(r+h)\) \(2\),\(\pi\) \(r\),\(h\) b. \(2(L + W)\) \(2\) \(L\), \(W\) c. \(4y^3+y\) \(4\) \(y\)

Evaluate the expression \(2x−7\) for each value for \(x\).

- \(x=0\)

- \(x=1\)

- \(x=12\)

- \(x=−4\)

Solution

- Substitute \(0\) for \(x\). \[\begin{align*} 2x-7 &= 2(0)-7 \\ &= 0-7\\ &= -7\\ \end{align*}\]

- Substitute \(1\) for \(x\). \[\begin{align*} 2x-7 &= 2(1)-7 \\ &= 2-7\\ &= -5\\ \end{align*}\]

- Substitute \(\dfrac{1}{2}\) for \(x\). \[\begin{align*} 2x-7 &= 2\left (\dfrac{1}{2} \right )-7 \\ &= 1-7\\ &= -6\\ \end{align*}\]

- Substitute \(-4\) for \(x\). \[\begin{align*} 2x-7 &= 2(-4)-7 \\ &= -8-7\\ &= -15\\ \end{align*}\]

Evaluate the expression \(11−3y\) for each value for \(y\).

- \(y=2\)

- \(y=0\)

- \(y=\dfrac{2}{3}\)

- \(y=−5\)

- Answer

-

- \(11\)

- \(26\)

Evaluate each expression for the given values.

- \(x+5\) for \(x=-5\)

- \(\dfrac{t}{2t-1}\) for \(t=10\)

- \(\dfrac{4}{3}\pi r^3\) for \(r=5\)

- \(a+ab+b\) for \(a=11\), \(b=-8\)

- \(\sqrt{2m^3 n^2}\) for \(m=2\), \(n=3\)

Solution

- Substitute

\(-5\) for \(x\). \[\begin{align*} x+5 &= (-5)+5 \\ &= 0\\ \end{align*}\] - Substitute \(10\) for \(t\). \[\begin{align*} \dfrac{t}{2t-1} &= \dfrac{(10)}{2(10)-1} \\ &= \dfrac{10}{20-1}\\ &= \dfrac{10}{19}\\ \end{align*}\]

- Substitute \(5\) for \(r\)

. \[\begin{align*} \dfrac{4}{3} \pi r^3 &= \dfrac{4}{3}\pi (5)^3 \\ &= \dfrac{4}{3}\pi (125)\\ &= \dfrac{500}{3}\pi\\ \end{align*}\] - Substitute \(11\) for \(a\) and \(-8\) for \(b\)

. \[\begin{align*} a+ab+b &= (11)+(11)(-8)+(-8) \\ &= 11-88-8 \\ &= -85\\ \end{align*}\] - Substitute \(2\) for \(m\) and \(3\) for \(n\). \[\begin{align*} \sqrt{2m^3 n^2} &= \sqrt{2(2)^3 (3)^2} \\ &= \sqrt{2(8)(9)} \\ &= \sqrt{144} \\ &= 12 \end{align*}\]

Evaluate each expression for the given values.

- \(\dfrac{y+3}{y-3}\) for \(y=5\)

- \(7-2t\) for \(t=-2\)

- \(\dfrac{1}{3}\pi r^2\) for \(r=11\)

- \((p^2 q)^3\) for \(p=-2\), \(q=3\)

- \(4(m-n)-5(n-m)\) for \(m=\dfrac{2}{3}\) \(n=\dfrac{1}{3}\)

- Answer

-

- \(4\)

- \(11\)

- \(\dfrac{121}{3}\pi\)

- \(1728\)

- \(3\)

Formulas

An equation is a mathematical statement indicating that two expressions are equal. The expressions can be numerical or algebraic. The equation is not inherently true or false, but only a proposition. The values that make the equation true, the solutions, are found using the properties of real numbers and other results. For example, the equation \(2x +1= 7\) has the unique solution of \(3\) because when we substitute \(3\) for \(x\) in the equation, we obtain the true statement \(2(3)+1=7\).

A formula is an equation expressing a relationship between constant and variable quantities. Very often, the equation is a means of finding the value of one quantity (often a single variable) in terms of another or other quantities. One of the most common examples is the formula for finding the area \(A\) of a circle in terms of the radius \(r\) of the circle: \( A= \pi r^2\). For any value of \(r\), the area \(A\) can be found by evaluating the expression \(\pi r^2\).

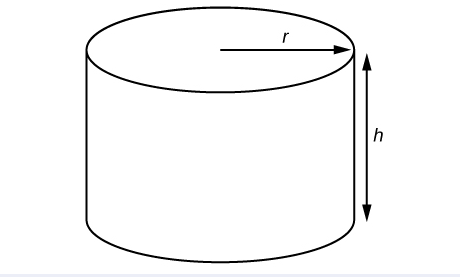

A right circular cylinder with radius \(r\) and height \(h\) has the surface area \(S\) (in square units) given by the formula \(S=2\pi r(r+h)\). See Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\). Find the surface area of a cylinder with radius \(6\) in. and height \(9\) in. Leave the answer in terms of \(\pi\).

Evaluate the expression \(2\pi r(r+h)\) for \(r=6\) and \(h=9\).

Solution

\[\begin{align*} S &= 2\pi r(r+h) \\ &= 2\pi (6)[(6)+(9)] \\ &= 2\pi(6)(15) \\ &= 180\pi \end{align*}\]

The surface area is \(180\pi\) square inches.

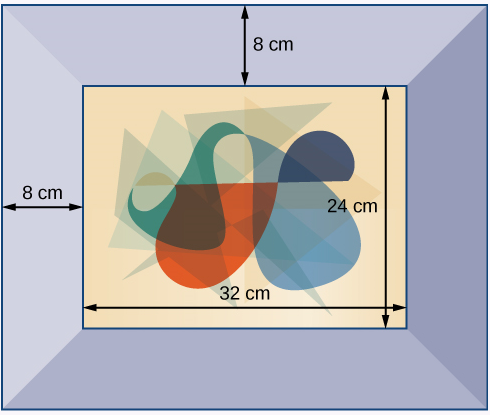

A photograph with length \(L\) and width \(W\) is placed in a matte of width \(8\) centimeters (cm). The area of the matte (in square centimeters, or \(cm^2\) is found to be \(A=(L+16)(W+16) - L\)⋅W

- Answer

-

\(1152cm^2\)

Simplifying Algebraic Expressions

Sometimes we can simplify an algebraic expression to make it easier to evaluate or to use in some other way. To do so, we use the properties of real numbers. We can use the same properties in formulas because they contain algebraic expressions.

Simplify each algebraic expression.

- \(3x-2y+x-3y-7\)

- \(2r-5(3-r)+4\)

- \(\left(4t-\dfrac{5}{4}s\right)-\left(\dfrac{2}{3}t+2s\right)\)

- \(2mn-5m+3mn+n\)

Solution

- \[\begin{align*} 3x-2y+x-3y-7&=3x+x-2y-3y-7 && \qquad \text{Commutative property of addition}\\ &=4x-5y-7 && \qquad \text{Simplify}\\ \end{align*}\]

- \[\begin{align*} 2r-5(3-r)+4&=2r-15+5r+4 && \qquad \qquad \qquad \text {Distributive property}\\ &=2r+5y-15+4 && \qquad \qquad \qquad \text{Commutative property of addition}\\ &=7r-11 && \qquad \qquad \qquad \text{Simplify}\\ \end{align*}\]

- \[\begin{align*} \left(4t-\dfrac{5}{4}s\right)-\left(\dfrac{2}{3}t+2s\right)&=4t-\dfrac{5}{4}s-\dfrac{2}{3}t-2s && \qquad \text{Distributive property}\\ &=4t-\dfrac{2}{3}t-\dfrac{5}{4}s-2s && \qquad \text{Commutative property of addition}\\ &=\dfrac{10}{3}t-\dfrac{13}{4}s && \qquad \text{Simplify}\\ \end{align*}\]

- \[\begin{align*} 2mn-5m+3mn+n&=2mn+3mn-5m+n && \qquad \text{Commutative property of addition}\\ &=5mn-5m+n && \qquad \text{Simplify}\\ \end{align*}\]

Simplify each algebraic expression.

- \(\dfrac{2}{3}y−2\left(\dfrac{4}{3}y+z\right)\)

- \(\dfrac{5}{t}−2−\dfrac{3}{t}+1\)

- \(4p(q−1)+q(1−p)\)

- \(9r−(s+2r)+(6−s)\)

- Answer

-

- \(−2y−2z\) or \(−2(y+z)\)

- \(\dfrac{2}{t}−1\)

- \(3pq−4p+q\)

- \(7r−2s+6\)

A rectangle with length \(L\) and width \(W\) has a perimeter \(P\) given by \(P =L+W+L+W\). Simplify this expression.

Solution

\[\begin{align*} P &=L+W+L+W\\ P &=L+L+W+W && \qquad \text{Commutative property of addition}\\ P &=2L+2W && \qquad \text{Simplify}\\ P &=2(L+W) && \qquad \text{Distributive property} \end{align*}\]

If the amount \(P\) is deposited into an account paying simple interest \(r\) for time \(t\), the total value of the deposit \(A\) is given by \(A =P+Prt\). Simplify the expression. (This formula will be explored in more detail later in the course.)

- Answer

-

\(A=P(1+rt)\)

Access these online resources for additional instruction and practice with real numbers.

Key Concepts

- Rational numbers may be written as fractions or terminating or repeating decimals. See Example and Example.

- Determine whether a number is rational or irrational by writing it as a decimal. See Example.

- The rational numbers and irrational numbers make up the set of real numbers. See Example. A number can be classified as natural, whole, integer, rational, or irrational. See Example.

- The order of operations is used to evaluate expressions. See Example.

- The real numbers under the operations of addition and multiplication obey basic rules, known as the properties of real numbers. These are the commutative properties, the associative properties, the distributive property, the identity properties, and the inverse properties. See Example.

- Algebraic expressions are composed of constants and variables that are combined using addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. See Example. They take on a numerical value when evaluated by replacing variables with constants. See Example,Example, and Example

- Formulas are equations in which one quantity is represented in terms of other quantities. They may be simplified or evaluated as any mathematical expression. See Example and Example.

Glossary

- algebraic expression

- constants and variables combined using addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division

- associative property of addition

- the sum of three numbers may be grouped differently without affecting the result; in symbols,a+(b+c)=(a+b)+c

- associative property of multiplication

- the product of three numbers may be grouped differently without affecting the result; in symbols,a⋅(b⋅c)=(a⋅b)⋅c

- base

- in exponential notation, the expression that is being multiplied

- commutative property of addition

- two numbers may be added in either order without affecting the result; in symbols,a+b=b+a

- commutative property of multiplication

- two numbers may be multiplied in any order without affecting the result; in symbols,a⋅b=b⋅a

- constant

- a quantity that does not change value

- distributive property

- the product of a factor times a sum is the sum of the factor times each term in the sum; in symbols,a⋅(b+c)=a⋅b+a⋅c

- equation

- a mathematical statement indicating that two expressions are equal

- exponent

- in exponential notation, the raised number or variable that indicates how many times the base is being multiplied

- exponential notation

- a shorthand method of writing products of the same factor

- formula

- an equation expressing a relationship between constant and variable quantities

- identity property of addition

- there is a unique number, called the additive identity, 0, which, when added to a number, results in the original number; in symbols,a+0=a

- identity property of multiplication

- there is a unique number, called the multiplicative identity, 1, which, when multiplied by a number, results in the original number; in symbols,a⋅1=a

- integers

- the set consisting of the natural numbers, their opposites, and 0:{…,−3,−2,−1,0,1,2,3,…}

- inverse property of addition

- for every real numbera,there is a unique number, called the additive inverse (or opposite), denoted−a,which, when added to the original number, results in the additive identity, 0; in symbols,a+(−a)=0

- inverse property of multiplication

- for every non-zero real numbera,there is a unique number, called the multiplicative inverse (or reciprocal), denoted1a,which, when multiplied by the original number, results in the multiplicative identity, 1; in symbols,a⋅1a=1

- irrational numbers

- the set of all numbers that are not rational; they cannot be written as either a terminating or repeating decimal; they cannot be expressed as a fraction of two integers

- natural numbers

- the set of counting numbers:{1,2,3,…}

- order of operations

- a set of rules governing how mathematical expressions are to be evaluated, assigning priorities to operations

- rational numbers

- the set of all numbers of the formmn,wheremandnare integers andn≠0.Any rational number may be written as a fraction or a terminating or repeating decimal.

- real number line

- a horizontal line used to represent the real numbers. An arbitrary fixed point is chosen to represent 0; positive numbers lie to the right of 0 and negative numbers to the left.

- real numbers

- the sets of rational numbers and irrational numbers taken together

- variable

- a quantity that may change value

- whole numbers

- the set consisting of 0 plus the natural numbers:{0,1,2,3,…}