2.3: Інфрачервона (ІЧ) спектроскопія - дивлячись на молекулярні коливання

- Page ID

- 25073

До теперішнього часу ми концентрувалися на поглинанні (і викиді) енергії, пов'язаної з переходами електронів між квантованими енергетичними рівнями. Однак, як ми обговорювали раніше, електронні енергії не є єдиними квантованими енергіями на атомному/молекулярному рівні. У молекулах квантуються як вібрації, так і обертання, але задіяні енергії набагато нижчі, ніж ті, які необхідні для розриву зв'язків. Почнемо з найпростішої з молекулярних систем, що складаються з двох атомів, пов'язаних між собою. У такій системі атоми можуть переміщатися взад-вперед відносно один одного по осі зв'язку (коливань). Коли вони вібрують і змінюють частоти обертання (і напрямки), потенційна енергія системи змінюється (Чому це так? Які фактори впливають на ці зміни?). Існують також рухи, пов'язані з обертаннями навколо облігацій. Але (дивно, і квантово-механічно) замість того, щоб мати можливість приймати будь-яке значення, енергії цих вібрацій (і обертань) також квантуються. Енергетичні проміжки між коливальними енергетичними станами, як правило, знаходяться в діапазоні інфрачервоного випромінювання. Якщо три і більше атомів з'єднані між собою, молекула також може згинатися, змінюючи кут зв'язку або форму молекули. [6]

Інфрачервоне випромінювання має меншу енергію, ніж видиме світло (довша довжина хвилі, менша частота). Ви, напевно, знайомі з інфрачервоними тепловими лампами, які використовуються для зігрівання та окулярів нічного бачення, які дозволяють власнику «бачити» вночі. [7] Нагадаємо, що об'єкти мають тенденцію випромінювати випромінювання (явище називається випромінюванням чорного тіла), оскільки кінетична енергія атомів і молекул в об'єкті перетворюється в електромагнітне випромінювання. Близько 300K (кімнатна температура або температура тіла) випромінювання, що випромінюється, знаходиться в ІЧ-області спектра. [8] І навпаки, коли ІЧ-випромінювання падає на нашу шкіру, ми відчуваємо це як зігріваюче відчуття, головним чином тому, що воно змушує молекули в нашій шкірі вібрувати і обертатися - збільшуючи кінетичну енергію і, отже, температуру.

Коли ми досліджуємо світло, що поглинається або випромінюється, коли молекули зазнають коливальних змін енергії, він відомий як інфрачервона спектроскопія. [9] Чому, ви можете запитати, ми зацікавлені в коливаннях молекул? На вібрації, обертання і згинальні рухи молекул впливає структура молекули в цілому (а також її оточення). Результатом є те, що багато молекул та фрагментів молекул мають дуже характерні схеми поглинання ІЧ, які можна використовувати для їх ідентифікації. Інфрачервона спектроскопія дозволяє ідентифікувати речовини на основі закономірностей в лабораторії і, наприклад, в міжзоряних пилових хмарах. Наявність досить складних молекул у космосі (сотні мільйонів світлових років від землі) було виявлено за допомогою ІЧ-спектроскопії.

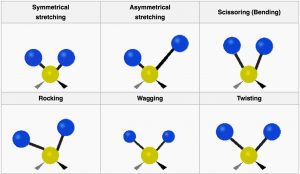

Типи змін, які можна виявити за допомогою ІЧ-спектроскопії, пов'язані як з розтягуванням (коливаннями) однієї конкретної зв'язку, так і з рухами, пов'язаними з трьома і більше атомами, такими як згинання або скручування. Розглянемо метан, наприклад: Кожен\(\mathrm{C-H}\) зв'язок може вібрувати окремо, але ми також можемо уявити, що вони можуть вібрувати «у фазі» (одночасно), щоб\(\mathrm{C-H}\) зв'язки подовжувалися і скорочувалися одночасно. Цей рух називається симетричним розтягуванням. І навпаки, ми можемо уявити, що один може подовжуватися, коли інший скорочується: це називається асиметричним розтягуванням. Крім того, молекула може згинатися і скручуватися різними способами, так що існує досить багато можливих «коливальних режимів». [10]

Коливальні режими СН 2

Тут ми бачимо коливальні режими для частини органічної молекули з\(\mathrm{CH}_{2}\) group. Not all these modes can be observed through infrared absorption and emission: vibrations that do not change the dipole movement (or charge distribution) for the molecules (for example, the symmetrical stretch) do not result in absorption of IR radiation, but since there are plenty of other vibrational modes[11] we can always detect the presence of symmetrical molecules like methane (and most other molecules) by IR spectroscopy. In addition, the more the charge distribution changes as the bond stretches, the greater the intensity of the peak. Therefore, as we will see, polar molecules tend to have stronger absorptions than non-polar molecules.

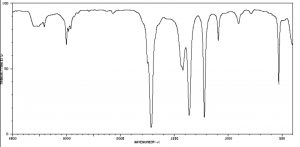

For historical reasons, IR spectra are typically plotted as transmittance (that is the amount of light that is allowed through the sample) versus wavenumber (\(\mathrm{cm}^{-1}\)).[12] That is, the peaks are inverted, so that at the top of the spectrum 100% of the light is transmitted and at the bottom it is all absorbed.

The position of the absorption in an IR spectrum depends three main factors:

- Bondstrength: it makes sense that the energy needed to stretch a bond (i.e. make it vibrate) depends on the strength of the bond. Therefore, multiple bonds appear at higher frequency (wavenumber) than single bonds.

- Whether the vibrations involved involve bond stretching or bending: it is easier to bend a molecule than to stretch a bond.

- The massesoftheatoms in a particular bond or group of atoms: bonds to very light atoms (particularly appear at higher frequency).[13]

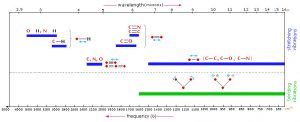

The figure below shows each of the general areas of the IR spectrum and the types of bonds that give rise to absorptions in each area of the spectrum. In general \(\mathrm{C-H}\), \(\mathrm{O-H}\), and \(\mathrm{N-H}\) bond stretches appear above \(3000 \mathrm{ cm}^{-1}\). Between \(2500\) and \(2000\) is typically where triple-bond stretches appear. Between \(2000\) and \(1500 \mathrm{ cm}^{-1}\) is the region where double-bond stretches appear, and the region below \(1600\) is called the fingerprint region. Typically, there are many peaks in this fingerprint region which may correspond to \(\mathrm{C-C}\), \(\mathrm{C-O}\) and \(\mathrm{C-N}\) stretches and many of the bending modes. In fact, this region is usually so complex that it is not possible to assign all the peaks, but rather the pattern of peaks may be compared to a database of compounds for identification purposes.

Vibrational Frequencies for Common Bond Types or Functional Groups

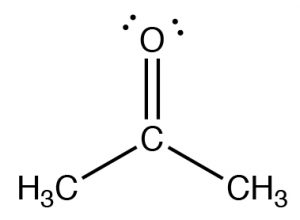

The figure below (\(\downarrow\)) shows a spectrum of acetone (\(\rightarrow\)) in which you can see a number of absorptions, the strongest of which appears around \(1710 \mathrm{ cm}^{-1}\). Note also that there is a discontinuity in scale above and below \(2000 \mathrm{ cm}^{-1}\). The strong peak around \(1710 \mathrm{ cm}^{-1}\) can be ascribed to one particular part of the acetone molecule: the \(\mathrm{C=O}\) (or carbonyl) group. It turns out that carbonyl groups can be identified by the presence of a strong peak in this region although the wavenumber of absorption may change a little depending on the chemical environment of the carbonyl. The presence of a strong peak between around \(1700 \mathrm{ cm}^{-1}\) almost always signifies the presence of a \(\mathrm{C=O}\) group within the molecule, while its shift from \(1700 \mathrm{ cm}^{-1}\) is influenced by the structure of the rest of the molecule.